Over on my other blog, I don’t make it much of a secret that I’m fascinated by startup stories. One of the things I’ve been trying to bring from that world into my classroom is the process of refinement that you can read about in Silicon Valley.

What doesn’t happen in Silicon Valley

If most people are like me, they think that some nerd has this great idea (probably while sitting in his parents’ basement, right?) and sits down to start coding. A few weeks, months, or years later, the next Instagram is born.

There’s this sense that the idea came fully formed into someone’s head–or was developed in one epic brainstorming meeting–and was set into the world the way it is.

What happens in Silicon Valley

Instead, what seems to emerge from the stories we hear about product development is this: someone has an idea (often because they realize they’d like to have a certain product to make their own work easier).

That person sits down and makes what Silicon Valley calls a “minimum viable product,” which is the fancy way of saying “the very least that anyone can do and still put it in front of customers.”

Then, the minimum viable product is presented to customers and, if they like it enough to use it, it will be developed further.

First lesson: lots of things are abandoned

It makes sense that we wouldn’t know about the thousands of idea that never get past the minimum viable product phase. After all, if nobody is interested in using it, how would we ever hear about them? For every Facebook, Instagram, or Tinder, there are thousands of things that have been tried and abandoned.

Second lesson: things are refined

Once users start using a Minimum Viable Product, it seems as though they take over development. One popular way of approaching product development says “you shouldn’t develop features until your users ask for them.”

So, as people are using this product, they are routinely contacting the startup behind it and tell them how to make it better.

Even more, the producers are constantly testing new ideas.

Any time you log into a website that has a pretty solid team behind it, there’s a good chance that you’re part of an experiment and you don’t even know it. Anytime the Googles and Facebooks of the world want to tweak the texts of their websites, they try out two different versions and deliver them both to thousands or millions of people… and then measure how the people reacted.

It’s called A/B testing (Which is better? A? or B?). And, because every minor change is rigorously tested, you don’t notice it: instead, you see a well-designed product.

My lessons

There was a time — only weeks ago — that I tried to make lessons according to the “produce it fully-formed and without any customer feedback” philosophy. And this resulted in some amazing lessons.

The fully-formed lesson

Often it’s made on Sunday in a panic: tomorrow the week starts and I need some great material for my conversation courses. With a bit of work, I would put something together and, improving in my delivery as the week continued, give the same lesson again and again.

Perhaps a student would discover a phrasing that I should have used (“It would be more clear if you just said ‘like a grandpa’.”) or I’d stumble upon a joke I should have incorporated in the text. (You can never have too many jokes!) But it would be too late: the lesson was prepared and I didn’t have a lot of time between lessons (and family) to really sit down and redo materials on most days.

The incrementally improved lesson

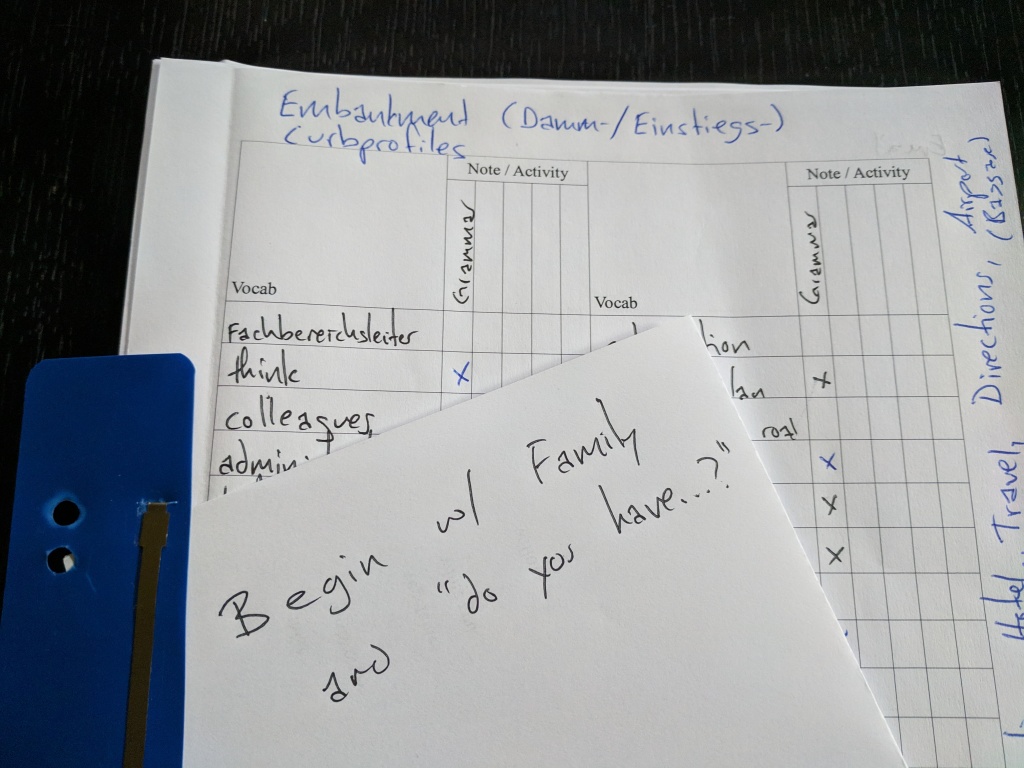

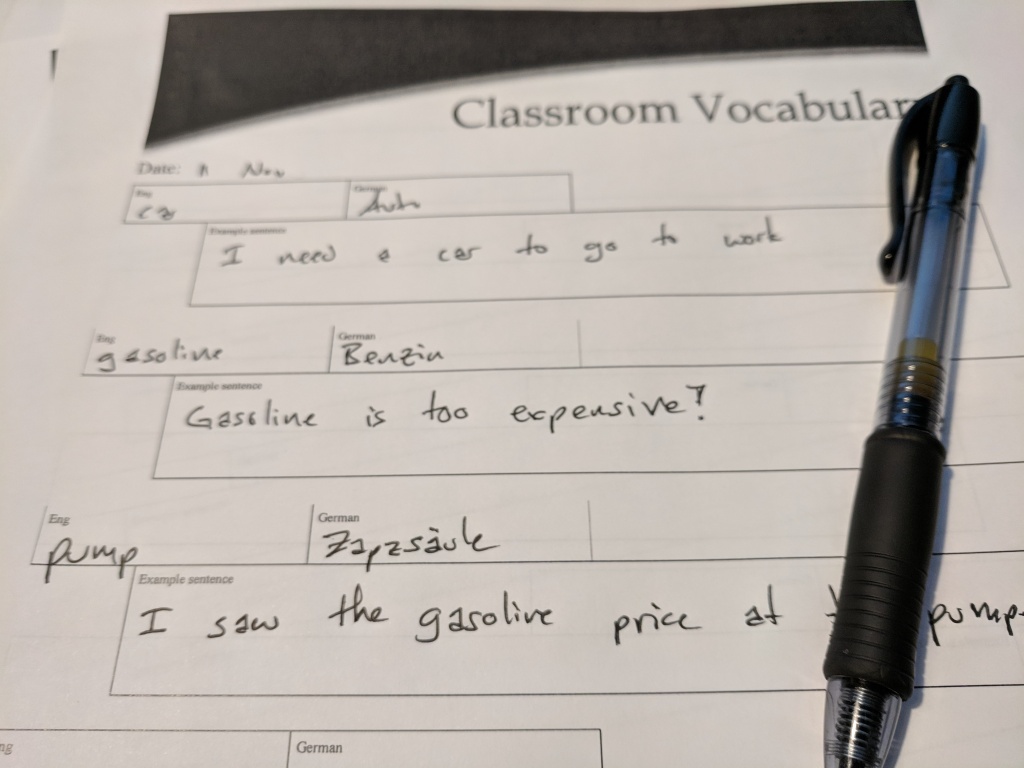

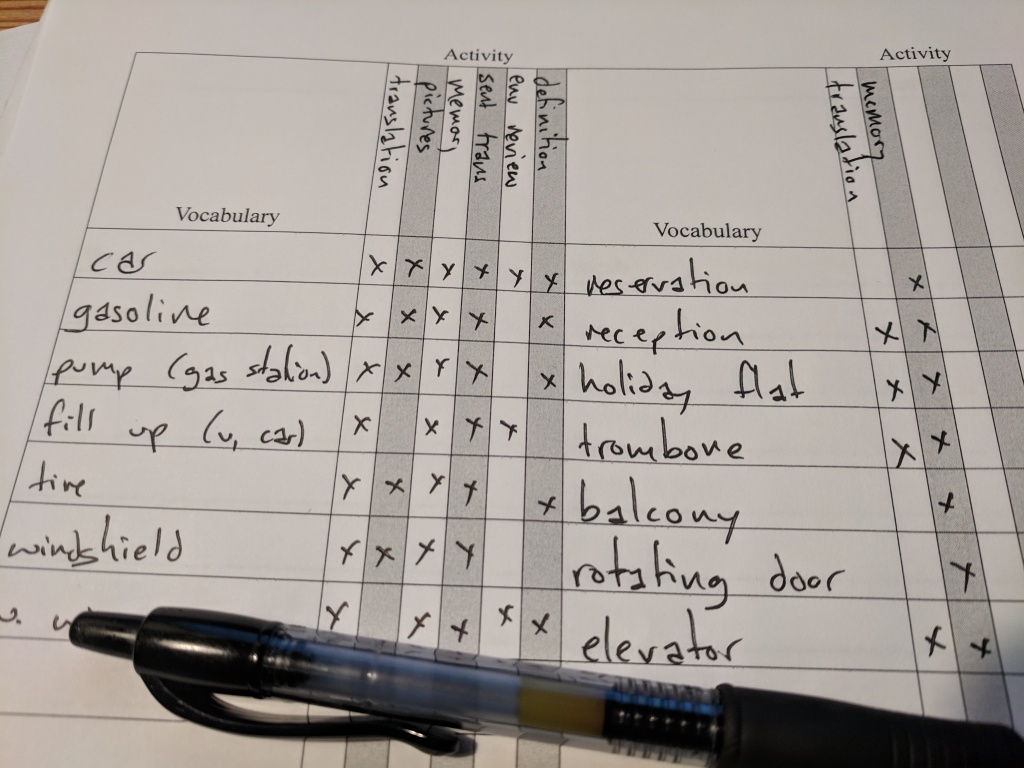

The strategy I’m trying for now, when my time allows me, is to prepare a few good ideas and make up a minimum viable set of worksheets and ideas.

Armed with these ideas and materials, I go into a classroom and give the best lesson I can under the circumstances. All the while I’m teaching and leading a conversation, I’m marking my copy of the materials with the ideas I’m having: something isn’t clear enough, another part doesn’t seem to interest the group…

Then, I plan to have enough time to update the materials and my ideas before I take it into the next class. Often, that can mean that I teach a lesson only once per week. Each week, it improves, though.

What do you think?

Is this something that you already do? (Often, I think I’ve found a new, great idea only to realize it was a well-established best practice.) What are ideas that you’ve refined through teaching? And — here’s my next question — how do you share great lessons that you’ve prepared?